“What do you want for your birthday?” I asked my Lina.

“An adventure.”

I pulled some levers, pushed some buttons, and made a plan.

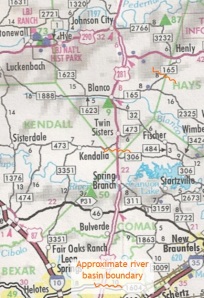

Sunday, February 16, 2020. We headed NW on US 183. This was a pleasure trip for ourselves, and I was also keen to preview a new route to West Texas that skips Johnson City and Fredericksburg. Since we abide on Austin’s northeast side, it was refreshing to bypass downtown and Oak Hill traffic.

Sailing was smooth to Seward Junction, where we bore left onto TX 29 and continued through Liberty Hill, Bertram, and Burnet. I pointed out RR 2341, which leads to Reveille Hill Ranch, the site of Utopia Fest each November. Right along there, the rocks dramatically changes from Cretaceous limestone to much older sandstone and granite.

The highway dipped into the Colorado River valley and curved past multiple-arched Buchanan Dam, built in 1937, the first of the Highland Lakes chain. Bluebonnet Lighthouse stands tall here and prevents pleasure craft from running aground. Over a crest, we hugged a railroad and the Llano River and followed both into that city—a misnomer, because llano means flat plain, which this area isn’t.

Across Willow Creek is Art, Texas, with its impressive red-stone Methodist Church and crescent of picnic table shelters. Then came the town of Mason and its cute courthouse square. No time to explore, we turned south onto US 377 and were impressed by the boulder-strewn landscape near Wolf Caves Rock Crawling Park, a pleasure property for off-road vehicles. London, Texas, came next and, sure enough, it flaunts a pub. An oddly shaped lone hill stood to our right, which we later identified as Teacup Mountain, so named for what it resembles.

In Junction, two branches of the Llano River come together. We stuck with the south fork, one of only a few Texas streams that flows north. Past a state park, we paused to read the historical marker at Telegraph: Here crews felled trees in the mid-19th century to use for telegraph poles. A post office and general store stand boarded up. Not far was former Texas governor Coke Stevenson’s ranch.

The pavement narrowed as we climbed in altitude up onto the top of the Edwards Plateau. Vegetation thinned, offering us sweeping views. From this rolling landscape, many of Texas’ prettiest rivers begin their plunge into the Hill Country, especially the Nueces—that’s nuts, to you.

Pulling into Rocksprings, elevation 2,450 feet, we were gratified to learn that not one traffic light exists in Edwards County. Diagonally to the courthouse, we found our name on an envelope taped to the front door of the Historic Rocksprings Hotel, built 1916. The keys were under the mat. We had just enough time to stash our bags in our upstairs room before rolling one block south.

Inside the Visitors Center, we relished homemade-bread sandwiches, watched introductory videos of Devil’s Sinkhole (the day’s main attraction), and purchased tickets from a young clerk. Her dad, Andrew, soon appeared and would be our guide. They are both volunteer members of the Devil’s Sinkhole Society, which organizes outings and events. He finished the flicks, adding detail and logistics.

We boarded our vehicle and followed him in his. With his phone linked to our sound system, Andrew led us on a tour of the town, pointing out the American Angora Goat Breeders’ Association headquarters and the county jail, which sports a tower for hangings that have never happened. Only a few structures, our hotel for one, survived the fierce April 12, 1927, F5 tornado, which razed nearly all of the village in only five minutes. Alas, the burg’s original namesake springs no longer flow much. Shortly we were heading north on 377 and out of signal range.

A locked gate allows only guided groups onto the 1,861-acre State Natural Area that embraces Devil’s Sinkhole. The well-paved road led us to park next to the remarkable feature. A sturdy platform let us peer, hesitatingly, into the 50-foot-wide maw and down into an abyss. No fair dropping mobile phones! The opening shaft plunges 100 feet to a jug-shaped cavity that deepens another 200 feet and widens to 1,081 feet. A cone of debris and guano forms Breakdown Mountain in the middle, made from material that fell when the ceiling collapsed. The hole’s three million-plus Mexican free-tail bats had gone south for the winter. When in residence, 300 of them manage to occupy each square foot of surface. Bleachers sit to one side for folks to observe the bats’ swirling exit flight each evening during the warm months. On that late-winter afternoon, we espied a only few birds and and insects.

A retired high school English teacher, Andrew walked us around the property, pointing out local cacti and wildflowers and a bird-watching blind with a rainwater-collecting roof. The thin soils were still a bit wet from recent showers. Anywhere we saw limestone with a rusty-red tint was likely a native American hearth site. Such traces of former inhabitants were all around, but I wondered where those early nomads got their water. Our guide followed us out the gate and bid us adieu.

We returned to town and settled into Room 211, the Rancher Suite, at the hotel. On a building corner, the bedroom sported a king-sized bed, adequate TV, and walk-in closet. The anteroom featured a couple tables, cabinet, another walk-in closet, and various side and comfy chairs. The bathroom offered convenience, a sink, and a shower. Magazines and tourist brochures waited on the tables, mirroring all manner of books filling shelves in the hallways and lobby. Mrs. Mulligan, a lifelike, full-sized manikin, offered chocolates from a tray at the foot of the stairs, and her companion, James, held shot glasses behind the bar. There’s a breakfast room, formal dining room, sitting room, private dining area—all furnished in antiques. An efficient commercial kitchen was open for guests’ use. Verandas gave views of the courthouse square. As the motto attests, these lodgings are truly a quiet respite on top of the world.

We took a stroll around said square and read all the historical markers.

For supper, we walked three blocks to Vaquero’s Café for migas and pork chops. That place sold no alcoholic beverages, so on the way back we slipped into the Jailhouse Bar and Grill for beer and wine.

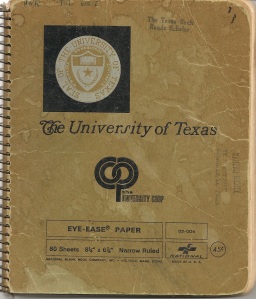

In the hotel we at last met Debra, our beaming hostess, who checked us in. Put the leftovers in a fridge and found the backstairs, which led straight to our suite. I read a gorgeous picture book on the frontier forts of Texas, which brought to mind a paper I’d written about the subject back in college and my travels to many of the sites. Tried watching movies in bed, but could find nothing of interest. Sleep!

MoonDay, February 17, 2020. Foggy it was, and hushed in the hamlet, except for some white wings cooing, a rooster crowing, a hound barking, and an occasional motor vehicle passing. This day would have been our beloved Uncle Elmore’s 100th birthday. Lina made the first pot of coffee with our en-suite machine, and I supervised the second. We both journaled and did our morning yoga. Breakfast was leftovers from the previous evening, my first time ever to eat pork chops so early in a day. Check-out time was noon, but we felt a need to get back on the road sooner than that.

Packed and loaded, we breezed through the mist north on US 377, generally retracing our route from the day before. Time allowed us to explore all the places we’d merely passed through previously. We promptly left the plateau behind and curved along the river’s south prong, dropping in height and beholding valleys and hills. A scenic overlook afforded vistas of a wall of seeps just below. Back in the 1960s, Pearl Beer advertised itself as “brewed with pure artesian water from the country of 1100 springs,” and we figured they must’ve begun their count here. The map names such gushing features: Paint Rock Spring, Blue Hole on the Llano, Tanner Springs, Seven Hundred Springs, and Bowie Spring, among others. From these trickles comes a proud stream, and all that water eventually flows through Austin via the mighty Colorado.

Lina’s dad, like mine, made a point of reading all historical markers along the way during trips. We pulled over near Cajac Creek and learned about the Doom of the Outlaws of Pegleg Station, a gunfight in January of 1878 between Texas Rangers and Dick Dublin’s gang of murderous thieves. They were suspected of holding up several mail stagecoaches, especially near a travelers’ rest stop on the San Saba River by Robbers’ Roost east of Menard.

Next marker told of the Four Mile Dam which, in 1896, supplied water for irrigation and power. Too, we got a better gander at the unique bright red and white crumbly limestone strata here, revealed from roadcuts. Past the state park, we were in Junction.

One of my favorite landmarks here is Las Lomas Hotel, built in 1926 by former Texas governor Coke Stevenson. It was quite the party place during the Decade that Roared and later. The building seemed in good shape, but we found no signs of recent activity. I’d love to see a medallion, renovation, and reopening. We filled the tank with gasoline and continued.

Shortly came the historical marker for Reichenau Gap, a pass between mesas, named for a German pioneer who attempted to settle hereabouts. In London we made sure to photograph the pub, which sits by a park close to the high school. Ivy’s London Dance Hall sponsors live music every Saturday night. Ivy’s London Grocery and Grill supplies catfish on Fridays. Weekend away, anyone? A plaque fronting the Community Center discloses that the town was named for London, Kentucky. The crossroads had aspirations to be county seat. Astride the Western Cattle Trail between Bandera and Concho in the 1880s, Londoners ran businesses catering to cowboys and their ilk. Our very same Coke Stevenson lived here as a kid.

Mason calls itself the Gem of the Hill Country for its only-here blue topaz, state gem of Texas. Our Verizon phones didn’t work there. We went up the wrong slope looking for the old fort. Stopped into a thrift store for directions and to check out bargains. Half a block away was Post Hill Road, which ascended to a reconstruction of the officers’ quarters. It’s dogrun-style, meaning two rooms with a breezeway between and a common roof above.

Unlike the forts you see in movies, almost none in Texas was surrounded by a stockade. Exhibits told the story: Famous US Army generals, including Robert E. Lee, served here. We enjoyed town and countryside panoramic views, which would have been advantageous for a military installation. A model shows the original layout.

On the way down is the public library with a statue of Old Yeller out front. Author Fred Gibson was a native of Mason. Parked on the square (in truth a rectangle) and stepped into the Chamber of Commerce. Despite wanting to cut back on collecting paper, we left with a bundle of brochures, pamphlets, and maps regarding area attractions.

One block west was Square Plate Restaurant, where lunch consisted of sesame-fried chicken, deep green beans, rice, and tea. Yes, all meals were delivered on square plates. There was something gratifying about gazing across the courthouse lawn and seeing a windmill.

We steered the pickup north on Broad Street to ogle at the elegant Seaquist House from 1896. Utilizing the same kind of red sandstone as we saw in the fort, the design adds white limestone quoins for accent. Stained glass, carved rock, and wrap-around porches speak of craft and opulence. Several prominent families called the house home, but over time the palace fell into neglectful decay. A local foundation offers tours and is engaged in total restoration. Remarkable is the third-floor ballroom.

Eastbound on TX 29, we paused in Llano to check out the Dabbs Railroad Hotel. Built in 1906 when Llano was the terminus of the Austin and Northwestern Railroad, this rooming house catered to train company employees who would spend the night before returning eastward on the train the next day. Other folks could also stay there, the most notorious being Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow and their gang. Yours truly presented a talk about area geology and history here back in the 1990s. Today, the spiffed-up facility promotes itself as an event center for weddings, parties, and weekend getaways.

Keeping our pace, we breezed through Burnet and Liberty Hill and got back to our little Fig Cottage by late afternoon. Amazing what you can see in just a couple days’ drive around Central Texas.

Thanks for reading!

Day dawned by Fredericksburg, and the sprinkling abated. Seamlessly we merged onto good ol’ I-10 and attained 83 mph. By tradition, first stop is breakfast at our favorite café in Junction, where we arrived at 8:30. Helen is the very same waitress who’s worked there since I first began going west in the mid-1970s. She claims to remember me. The Junction Special consists of two of everything: bacon strips, sausages, pancakes, and eggs over easy—all washed down with steaming coffee.

Day dawned by Fredericksburg, and the sprinkling abated. Seamlessly we merged onto good ol’ I-10 and attained 83 mph. By tradition, first stop is breakfast at our favorite café in Junction, where we arrived at 8:30. Helen is the very same waitress who’s worked there since I first began going west in the mid-1970s. She claims to remember me. The Junction Special consists of two of everything: bacon strips, sausages, pancakes, and eggs over easy—all washed down with steaming coffee. After filling

After filling